When a Canadian quarterback beat the Hamilton Tiger-Cats — in a human rights case

Published July 20, 2022 at 1:09 pm

As Canadian quarterbacks, Nathan Rourke and Tre Ford have been sending football fact-checkers on deep routes this season.

The two 24-year-olds, one of whom will face the Hamilton Tiger-Cats on Thursday night and one who got his first CFL win against the Ticats on Canada Day, have achieved several first-Canadian-QB-since feats. Rourke, the Oakville native who starts for the B.C. Lions, set a record for passing yards in a game by a Canadian earlier this season. Ford, a Niagara Falls, Ont., native who is a rookie with the Edmonton Elks, is the first Black Canadian QB to start for the storied franchise, as well as its first Canadian QB in more than a half-century.

Little exposition is needed to understand why ‘QB1’ — and 2, and 3 — are almost always Americans. The United States has a football-industrial complex. Canadian football is more of a niche. There are only 27 football-playing schools in U Sports. Texas alone has more teams in the top three flights of U.S. college football (FBS, FCS and Division II).

Chris Flynn, another Great Canadian Hope, once explained that is comes down to numbers. Any Canadian passer who has the skills will be up against 50 American prospects. Also, the media and fans will be attentive about a QB from, say, McMaster. But they won’t notice if someone from Middle Tennessee State is here today and gone tomorrow.

One can see how that would foster an availability bias in CFL front offices, or in coachspeak, make a Canadian quarterback ‘a distraction.’ As a matter of fact, Jamie Bone actually proved that was the case. Only he did not prove it on a 110-yard-long field. Rather, he proved it in court.

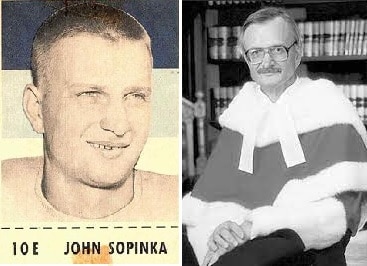

Forty-three years ago this month, Bone won a settlement from the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s board of inquiry, after charging that the Tiger-Cats had discriminated against him because he was a Canadian. Bone had a legal giant representing him — none other than John Sopinka, whose name might be recognizable since it graces the courthouse in downtown Hamilton.

For background, Bone led the Western Mustangs to consecutive Vanier Cup titles in 1976 and ’77. His play inspired talk of him being the next one, the great Canadian quarterback hope who would will a void left open since the end of the 1960s, when Ottawa Rough Riders great Russ Jackson (a Hamilton native) hung it up.

‘I didn’t want any Canadian quarterback to have to go through what I went through’

Bone went to the Tiger-Cats training camp in the spring of 1978. He found he was given half as many plays to run as two favoured Americans. At one point, he was told by the general manager, “It takes a hell of a lot of guts for a coach to play a Canadian quarterback.” He was cut after the first exhibition game, without getting to play in it, and none of the other eight CFL teams picked him off the waiver wire.

Pro football, as you hear from the studio panels every week, is a results-based business. Rules are usually made with an eye to what is best for the teams. In the CFL of the 1970s, that meant the import rules were twigged to allow a team to dress two American quarterbacks.

Under the rules of day, 10 of the 24 starters on defence and offence had to be non-imports. (Today, it’s seven.) The 15 import slots were typically taken up by the other 14 starters and the second-string quarterback, who was listed as a “designated import.” By the end of the decade, only one Canadian quarterback, Montreal Alouettes backup Gerry Dattilio, remained in the league.

Meantime, after being cut, Bone went back to Western for one more season and won the Hec Crighton Trophy, the award for the top university player in Canada that Ford won in 2021. As Maclean’s reported at the time, the treatment from the Tiger-Cats gnawed at him. A quarterback, to quote “North Dallas Forty” author Peter Gent, needs the “ability to be all things to all people.” In that regard, Bone had to step up, even if meant taking a hit.

As Bone told MacLean’s magazine: “I didn’t want to wake up five years from now wishing I’d done something then that I didn’t do. I didn’t want any Canadian quarterback to have to go through what I went through.” So that led to him filing the human rights case against the Tiger-Cats in the spring of 1979.

Sopinka, a Hamilton-raised lawyer and former CFL player, convened the board of inquiry and represented Bone. Sopinka had played the sport on a professional level. A decade later he would become the first Ukrainian-Canadian justice appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada, even though he had never been a judge. Between being an ex-player, and being from a people who had endured diaspora and displacement, Sopinka would have had some insight into how systemic exclusion works.

The league was essentially on trial. And Sopinka got Tom Dimitroff, the Tiger-Cats head coach who had cut Bone in 1978, to admit he had made up his mind about Bone before ever seeing him command a huddle and sling an oblong ball downfield.

“Ever candid, the veteran coach admitted he believed that U.S. players are superior to Canadians, mainly because they are better trained at the high-school and college levels,” Derm Dunwoody wrote in the Aug. 13, 1979, issue of Canada’s national newsweekly. “He then conceded he had made up his mind that Bone wasn’t going to be his quarterback long before the Canadian had reported to camp.” Dimitroff, in a prior conversation with the human rights commission, had also said he was “simply taken advantage” of the designated-import rule that “all the other coaches” were using in order to have two American quarterbacks.

Tryout with the Cowboys

The board of inquiry awarded Bone $10,000 (about $38,000 today) and ordered the Tiger-Cats to offer him a 30-day tryout. Bone declined the tryout, perhaps well-aware that a bridge had been burned.

Denied his fair shot Canada, Bone did get validation from America’s Team. In 1980, the Dallas Cowboys saw enough from Western game film and a scouting trip up to London, Ont., that they signed Bone as a free agent.

Bone spent about four months on the Dallas roster before being cut. Hall of famer Roger Staubach had just retired, but the Cowboys were deep at quarterback. Famed coach Tom Landry ended up going with Danny White, Gary Hogeboom and Glenn Carano (father of actress and MMA fighter Gina Carano) that season.

The CFL later changed the rules to exempt quarterbacks from its national/international player rules. Playing quarterback would have to be aspirational for a Canadian. The advent of more specialized coaching, better sport-specific training and some well-funded university teams created a support system that has supported a few players who have broken through the artificial-grass ceiling.

Bone is very much in that inner circle of Canadian quarterbacks who have legend status among a certain subset of football fans in Canada, recalled with a bit of of the what-might-have-been. Since many of these nationals only got a notional look from the CFL, or were thrown into the breach with a bad team, a lot of what they did is off the grid of YouTube compilations and media hype.

In 2014, Sportsnet ranked Bone as the 12th-best university player of the Vanier Cup era, which began in 1965. Only two quarterbacks — Flynn and Greg Vavra — were ranked higher on that list.

The first-Canadian-QB-sinces have been piling up steadily since 2015. Mississauga native Brandon Bridge achieved a few while playing for four teams over a five-season career. In 2016, Andrew Buckley, a Red Deer, Alta., native, became the first Canadian quarterback since Russ Jackson to score a touchdown in a Grey Cup game.

Out in Vancouver, the Lions have two Canadians behind centre since Rourke is backed up by Ottawa native Michael O’Connor. Ford is out of the Elks lineup with an injury to his throwing shoulder. But the notion of two Canadian QBs on one team, or one directly out of Ontario University Athletics starting in the CFL, would have been wishcasting not too long ago.

Both are just a bit older than Jamie Bone was when he took the CFL to court. And, fulfilling the hope he expressed at that time, neither have to go through what he did.

INthehammer's Editorial Standards and Policies