Lessons from Kate Crooks, trailblazing botanist from Niagara-on-the-Lake, who is buried in Hamilton

Published November 17, 2021 at 11:57 pm

Through Kate Crooks, and one researcher’s effort to dig up her work, there is a lesson about the value of preserving natural habitats and history. As it happens, Thursday is the eve of a decision that will shape all three in Hamilton for decades to come.

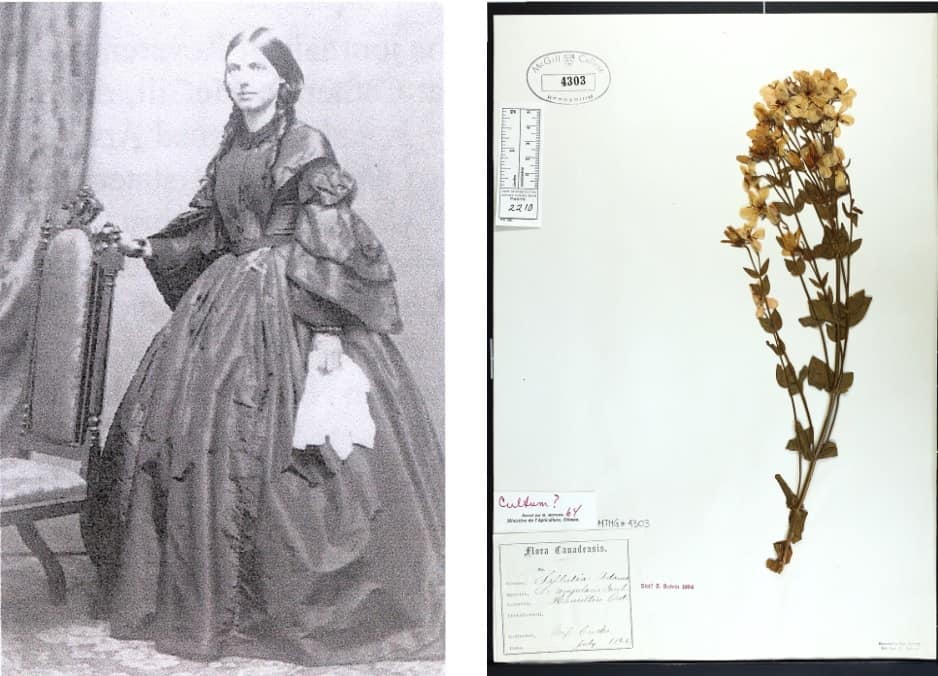

The Crooks name still has a place in modern-day Hamilton, through Crooks’ Hollow Conservation Area in the Dundas area. It is named for James Crooks, who built the area’s first gristmill. But his niece, Catharine McGill (Kate) Crooks (1833-1871), was a self-taught botanist who influenced biodiversity in mid-19th century Ontario, through her painstaking work collecting plant specimens in the Hamilton, Cambridge, London and St. Thomas areas.

And, even within the field of botany, Crooks’ contribution has all but vanished from collective memory. How that came to be puzzles Anna Soper, a librarian and gardener based in Kingston, Ont., who has made a project of trying to discover as much as possible about Crooks.

“It’s important to know about that history with Kate Crooks, and the contributions that she made, along with her brother-in-law, Alexander Logie,” says Soper, an avid gardener. “Many of the plants she found in southwestern Ontario still grow in the wild on either side of the Niagara Escarpment. Although some are now endangered or extinct in Ontario.”

Soper has written about Crooks’ work, and her effort to locate some of it, for Atlas Obscura, Biodiversity Heritage Library and Niche-Canada.

Soper is also active on iNaturalist, a social network favoured by citizen scientists where a member can take a picture of a unique plant with their phone and have it identified almost instantly.

Crooks was born in 1833 in the settlement of Newark, now Niagara-on-the-Lake. When she took to botany in her late 20s, she and Logie captured a record of Ontario’s flora in an era well before the automobile, industrialization and urban sprawl.

In 1861, they joined the nascent Botanical Society of Canada and presented it with a collection of Hamilton flora.

‘Unique in that women could join’

In 1862, Crooks’ herbarium of native Canadian flowers, shrubs and trees was shown in London, England in the International Exhibition of 1862. She received an honourable mention for her collection.

Soper notes that Crooks, and the Kingston-based Botanical Society of Canada, were progressive on gender equity.

“The Botanical Society of Canada was unique in that women could join,” Soper says. “Anyone could be a member as long as they contributed one piece of original research. There were similar scientific societies in Europe that did not admit women until well into the 20th century.”

Crooks’s death in 1871 came eight days after giving birth to her third child. She is interred in the main cemetery in Hamilton, along York Boulevard.

Soper came across Crooks in 2017, when she was collecting flora in Kingston as a way to mark the 150th anniversary of Canadian confederation.

Only one plant specimen that Crooks collected and pressed — a rose pink, discovered in Hamilton in 1865 — has been located. It is in the herbarium at McGill University in Montreal.

“It was so important to find that,” Soper says.

While not a scientist, Soper says some of the species that Crooks collected are found in the area where the Progressive Conservative government wants to build the controversial Highway 413. The $10-billion-plus project is opposed by several local governments and many environmentalists.

The previous Liberal government also considered the idea for over a decade before ditching it in 2018.

Hamilton’s elected leadership, of course, will vote on urban boundary expansion on Friday morning. City councillors will vote on whether to allow residential development on some 1,300 hectares of prime farmland, in order to accommodate growth over the next 30 years.

One or both becoming reality would likely wipe out a little more of what Kate Crooks catalogued a century and a half ago.

Soper, as noted, came to learn about Crooks through her own ‘Flora 150’ project that she started in Kingston in 2017, during Canada 150. And that project came to be since she walks to work, something many Hamiltonians might prefer to driving.

“I’m fascinated by urban wildflowers that, for instance, grow up against a chain-link fence or in a sun-trap at the side of a building. And you can see so much more when you’re walking as opposed to being in a car, or even on a bike.”

INthehammer's Editorial Standards and Policies